Imagine the sheer power of a cascading waterfall or a mighty river carving its path through a canyon. Now, imagine capturing a fraction of that natural force and transforming it into the electricity that lights our homes, powers our industries, and charges our devices. This isn't science fiction; it's the everyday marvel of Understanding Hydroelectric Generators. These impressive machines are the heart of hydropower plants, silently—or often, quite audibly—converting the simple flow of water into a reliable stream of electrical power.

If you’ve ever wondered about the intricate dance between water and wire that creates clean energy, you’re in the right place. We're going to pull back the curtain on how these essential pieces of our energy infrastructure function, why they're so vital to a sustainable future, and what makes them tick.

At a Glance: What You’ll Discover About Hydroelectric Generators

- Harnessing Water's Energy: Hydroelectric generators turn the potential energy of water, often stored behind a dam, into kinetic energy, then into mechanical motion, and finally into electricity.

- The Core Principle: This conversion relies on electromagnetic induction, a fundamental scientific discovery from the 19th century that lets us create electricity from moving magnets and coils.

- Key Components: From the water-driven turbine to the electricity-generating rotor and stator, each part plays a crucial role in the power creation process.

- Diverse Systems: Hydropower isn't a one-size-fits-all solution; it encompasses various turbine types and plant designs, including large dam systems, run-of-river setups, and even pumped storage for grid stability.

- Major Advantages: It's a clean, renewable, and remarkably reliable energy source that can respond quickly to demand and helps manage water resources.

- Significant Challenges: Building these plants requires substantial investment and can significantly alter natural ecosystems, necessitating careful planning and mitigation.

- A Bright Future: Ongoing innovation focuses on making hydropower even more efficient and environmentally friendly, solidifying its place in the global clean energy transition.

The Electrifying Core: How Water Becomes Watts

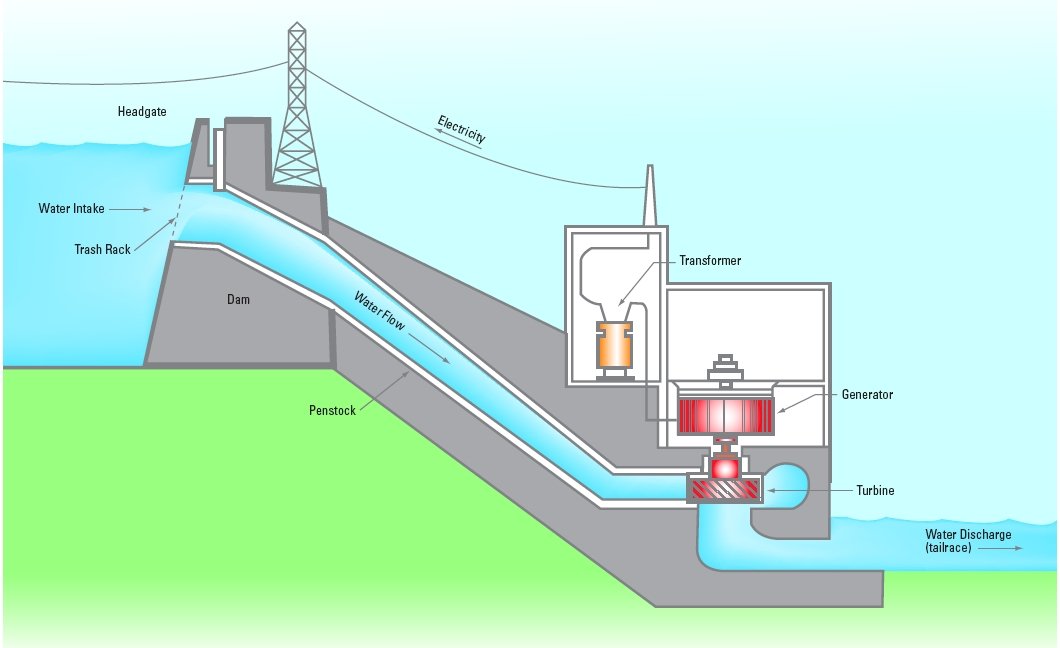

At its most fundamental level, a hydroelectric generator is a sophisticated energy converter. It doesn't create energy; it transforms it. The journey begins with water, typically held at a higher elevation, such as in a reservoir behind a dam. This elevated water possesses potential energy—energy by virtue of its position.

When this water is released, it flows downhill through a controlled channel called a penstock, gaining speed and converting its potential energy into kinetic energy—energy of motion. This fast-moving water is then directed at a turbine, the first hero in our story.

The Dance of Turbine, Shaft, and Generator

Imagine a massive pinwheel, but instead of wind, it's propelled by powerful jets or currents of water. That's essentially a turbine. As the water rushes past its blades, it transfers its kinetic energy, causing the turbine to spin with immense force. This mechanical energy is then transmitted via a sturdy shaft to the heart of the electrical generation: the generator itself.

Inside the generator, you'll find two main characters:

- The Rotor: This is the spinning part, directly connected to the turbine's shaft. It's essentially a giant electromagnet, or a series of electromagnets. As it spins, it creates a constantly changing magnetic field.

- The Stator: This is the stationary part of the generator, encircling the rotor. It's packed with tightly wound coils of copper wire.

Here’s where the real magic happens, thanks to a principle discovered by Michael Faraday in the 19th century: electromagnetic induction. As the rotor's magnetic field sweeps past the stator's wire coils, it induces an electrical voltage in those coils. This induced voltage drives an electrical current, and voilà—you have electricity! This intricate process is at the heart of electromagnetic induction in hydropower, enabling the conversion from mechanical motion to usable electrical power.

This newly generated electricity then travels through transformers to step up its voltage for efficient long-distance transmission via power lines, eventually reaching homes and businesses. It's a continuous, powerful cycle, driven by the very forces of nature. To dive deeper into the nuts and bolts of these remarkable systems, you can always Learn more about hydroelectric generators in detail.

Not All Water Wheels Are Created Equal: Types of Hydroelectric Turbines

Just as different rivers have different flows and different elevations, hydroelectric plants employ various turbine designs optimized for specific conditions. Choosing the right turbine is crucial for maximizing efficiency and power output. Broadly, we categorize them into two main types based on how they interact with water: Impulse and Reaction.

Impulse Turbines: The High-Velocity Punch

Impulse turbines are like a boxer delivering a sharp, focused punch. They operate best in "high-head" situations, meaning there's a significant drop in elevation from the water source to the turbine, resulting in very high water velocity.

- The Pelton Wheel: The most common impulse turbine is the Pelton wheel. Imagine a large wheel with a series of specially shaped buckets around its rim. High-pressure water jets are directed at these buckets, hitting them with force and causing the wheel to spin. Pelton wheels are incredibly efficient for very high heads and relatively low water flow rates, often found in mountainous regions.

Reaction Turbines: The Pressure Differential Push

Reaction turbines are more like a swimmer pushing off the wall—they harness the pressure difference of water flowing through them. They are ideal for "low-head" and "medium-head" applications where there's less elevation drop but often a higher volume of water flow.

- Francis Turbines: These are the workhorses of the hydropower world, suitable for a wide range of heads and flows. Water enters a Francis turbine in a spiral casing, flowing through guide vanes that direct it towards the runner (the spinning part). The water then changes direction, exiting through the center, and in doing so, creates a pressure drop across the runner blades, generating rotational force.

- Kaplan Turbines: Think of a Kaplan turbine like a ship's propeller, but in reverse. It's designed for very low-head, high-flow situations, often where rivers are wide and relatively flat. The blades of a Kaplan turbine can be adjusted, much like an airplane propeller, to optimize efficiency for varying water flows.

Understanding these different types of hydroelectric turbines is key to appreciating how engineers tailor hydropower solutions to diverse geographical and hydrological conditions.

Beyond the Turbine: Different Hydropower System Designs

The generator and turbine form the core, but the overall plant design also varies significantly depending on the available water resources and power generation goals.

Reservoir-Based Systems: The Dam's Domain

When most people think of hydropower, they picture a massive dam creating a large reservoir. These reservoir-based systems are the most common and often the largest.

- How They Work: A dam blocks a river, creating a reservoir of water upstream. Gates in the dam control the release of water, allowing it to flow through penstocks (large pipes) to the turbines below. The stored water provides a consistent and controllable supply, allowing operators to generate electricity on demand.

- Advantages: Reservoirs offer significant operational flexibility. They can store vast amounts of energy (as potential water), provide flood control, support irrigation, and even create recreational opportunities.

- Challenges: The construction of large dams can have substantial environmental and social impacts, including habitat alteration, displacement of communities, and changes to downstream river ecosystems. We’ll delve into the environmental impacts of large dam projects shortly.

Run-of-River Systems: Tapping Natural Flow

In contrast to the massive scale of reservoir systems, run-of-river systems harness the natural flow of a river with minimal alteration.

- How They Work: Instead of a large dam and reservoir, these systems typically use a smaller diversion weir or simply channel a portion of the river's flow through an intake structure. The water is then directed through a penstock to a turbine, after which it’s returned directly to the river downstream. There's little to no water storage.

- Advantages: They have a much smaller environmental footprint than large dam projects, disturbing aquatic ecosystems less significantly. They also typically have lower construction costs.

- Challenges: Power generation is entirely dependent on the river's natural flow, meaning output can fluctuate greatly with seasons and weather. They offer less flexibility than reservoir systems in meeting peak demand. For more details on these systems, exploring run-of-river hydropower systems can offer a clearer picture.

Pumped Storage Hydropower: The Grid's Battery

Pumped storage hydropower (PSH) is a unique and increasingly vital form of hydropower, acting less as a primary power generator and more as a massive, flexible energy storage system for the electrical grid.

- How They Work: A pumped storage plant features two reservoirs at different elevations. During times of low electricity demand (and often cheaper electricity prices, e.g., overnight), excess power from other sources (like wind or solar) is used to pump water from the lower reservoir to the upper one. When electricity demand is high, the stored water is released from the upper reservoir, flowing downhill through turbines to generate electricity, just like a conventional hydropower plant.

- Advantages: PSH provides crucial grid stability. It can store intermittent renewable energy (like solar or wind) and release it when needed, balancing supply and demand. It offers extremely fast response times, making it ideal for managing sudden changes in grid load.

- Challenges: These projects are capital-intensive and also require significant land use and water resources, with environmental considerations similar to conventional dams. Delve deeper into how this innovative approach works by reading about pumped storage hydropower.

Why Hydroelectric Generators Matter: The Untapped Power of Water

Hydroelectric generators aren't just fascinating feats of engineering; they are a cornerstone of modern energy infrastructure and a crucial player in the global shift towards sustainability.

A Renewable & Clean Energy Champion

One of the most compelling advantages of hydropower is its renewable nature. The water cycle—evaporation, condensation, precipitation, and flow—is a continuous, naturally recharging system. As long as rivers flow and rain falls, hydropower can be generated. Furthermore, once built, hydropower plants produce electricity with virtually no greenhouse gas emissions. Unlike fossil fuel power plants, they don't burn anything, eliminating carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and sulfur dioxide from the generation process. This makes them a vital tool in combating climate change and reducing our carbon footprint. This environmental benefit aligns perfectly with the broader benefits of renewable energy sources.

Unmatched Reliability and Stability

Unlike solar panels that only work when the sun shines or wind turbines that require a breeze, hydropower, especially reservoir-based systems, offers remarkable stability and reliability. The stored water in a reservoir acts like a massive battery, ready to be unleashed at a moment's notice.

- Grid Stabilization: This ability to control output makes hydropower invaluable for grid stability, providing base load power and rapidly adjusting to meet peak demand fluctuations.

- Quick Start-Up: Hydropower generators can go from idle to full power faster than almost any other conventional power source, making them excellent for responding to sudden surges in electricity demand.

- Long Lifespan: Hydroelectric plants are built to last, often operating efficiently for 50 to 100 years or more with proper maintenance, representing a significant long-term investment in energy infrastructure.

Economic and Environmental Co-Benefits

Beyond electricity generation, hydropower projects, especially those with reservoirs, often deliver multiple benefits:

- Flood Control: Dams can hold back excess water during heavy rainfall, preventing devastating downstream floods.

- Water Supply: Reservoirs serve as critical sources of drinking water, irrigation for agriculture, and industrial use.

- Navigation & Recreation: Navigable waterways can be created, and reservoirs often become popular sites for boating, fishing, and other recreational activities.

- Low Operating Costs: While initial construction is expensive, hydropower plants generally have very low operation and maintenance costs compared to thermal power plants, which require continuous fuel purchases.

The Downstream Ripple: Challenges and Considerations

Despite their numerous advantages, hydroelectric generators and the plants that house them are not without their complexities and drawbacks. Building and operating them requires careful consideration of their significant impacts.

High Upfront Costs and Long Timelines

Constructing a hydroelectric power plant, especially a large reservoir-based one, involves a massive financial outlay.

- Capital Intensive: The initial investment for dams, powerhouses, generators, and transmission infrastructure is substantial, often running into billions of dollars.

- Project Duration: These are not quick projects. Planning, environmental assessments, construction, and commissioning can take many years, sometimes even decades, from conception to completion. This long lead time means project viability must be assessed with a very long-term perspective.

Environmental and Ecological Alterations

Perhaps the most significant challenge associated with large-scale hydropower is its substantial alteration of natural water flow and ecosystems.

- Habitat Destruction and Fragmentation: Flooding vast areas to create reservoirs can destroy terrestrial habitats, submerge fertile land, and displace wildlife. The dam itself can act as a barrier, fragmenting aquatic habitats and preventing fish migration (e.g., salmon moving upstream to spawn).

- Changes to River Dynamics: Altering a river's natural flow regime—how much water flows, when, and at what temperature—can have profound effects downstream. This includes changes in sediment transport (which can starve downstream deltas of vital nutrients), water temperature fluctuations, and impacts on aquatic species adapted to specific flow patterns.

- Water Quality Impacts: Reservoirs can lead to stratification (layers of water with different temperatures and oxygen levels), affecting water quality. In some cases, decaying vegetation in newly flooded areas can release methane, a potent greenhouse gas, though the lifecycle emissions remain far lower than fossil fuels.

- Social Disruption: Large dam projects have historically led to the displacement of indigenous communities and local populations, necessitating careful and ethical resettlement planning.

Addressing these issues is paramount. Modern hydropower development often includes mitigation measures like fish ladders, environmental flow releases, and comprehensive impact assessments, but these efforts cannot always fully offset the ecological changes.

Looking Ahead: The Future of Hydroelectric Power

The future of hydroelectric generators is intrinsically linked to the global quest for cleaner, more sustainable energy. While the "easy" large-scale sites have largely been developed, innovation continues to drive the sector forward.

- Efficiency Improvements: Engineers are constantly refining turbine and generator designs to squeeze more electricity out of every drop of water, even at existing facilities. Advances in materials science and computational fluid dynamics allow for more efficient blade shapes and operational strategies.

- Small Hydro and Micro Hydro: A growing area of focus is on "small hydro" (typically under 30 MW) and "micro hydro" (under 100 kW) systems. These often involve run-of-river designs or leverage existing infrastructure (like irrigation canals) to generate electricity on a localized scale with minimal environmental impact. They are particularly promising for rural electrification in developing regions.

- Less Disruptive Designs: Research is exploring new ways to generate hydropower that are less invasive to natural river systems, focusing on technologies that can work with existing infrastructure or within natural river contours without the need for large dams.

- Pumped Storage Expansion: As renewable energy sources like solar and wind proliferate, the demand for flexible energy storage will skyrocket. Pumped storage hydropower is poised for significant expansion as a proven, large-scale battery for the grid, helping integrate intermittent power sources.

- Global Leaders: Countries like China, the United States, and Brazil continue to be major players in hydropower capacity, both in terms of existing infrastructure and ongoing development, demonstrating its enduring importance in diverse energy portfolios.

Hydroelectric generators are not just relics of the past; they are dynamic, evolving technologies critical to our energy present and future. They represent a powerful tool in reducing the carbon footprint of electricity generation, contributing significantly to climate change mitigation and ensuring global energy sustainability. As we continue to refine our understanding and technologies, the hum of the hydroelectric generator will remain a testament to humanity's ingenuity in harnessing nature's power responsibly.