Few energy sources can claim the steadfast reliability and monumental scale of hydropower. When we talk about generating clean electricity, the conversation invariably turns to the remarkable engineering behind types and applications of hydro generators. These aren't just massive machines; they're the heart of a system that has, for centuries, harnessed the raw, rhythmic power of flowing water to light our homes, fuel our industries, and increasingly, stabilize our modern grids.

Imagine a world powered by something as simple, ancient, and endlessly renewable as a river. That's the promise hydro generators deliver, transforming water's potential energy into the electrical power that underpins our civilization. It's a technology built on a fundamental principle – electromagnetic induction – and executed with a dazzling array of designs, each perfectly suited to a unique watery landscape.

At a Glance: Your Essential Hydro Generator Cheat Sheet

- How They Work: Water spins a turbine, which rotates a generator's rotor. This creates a changing magnetic field that induces electricity in stationary coils.

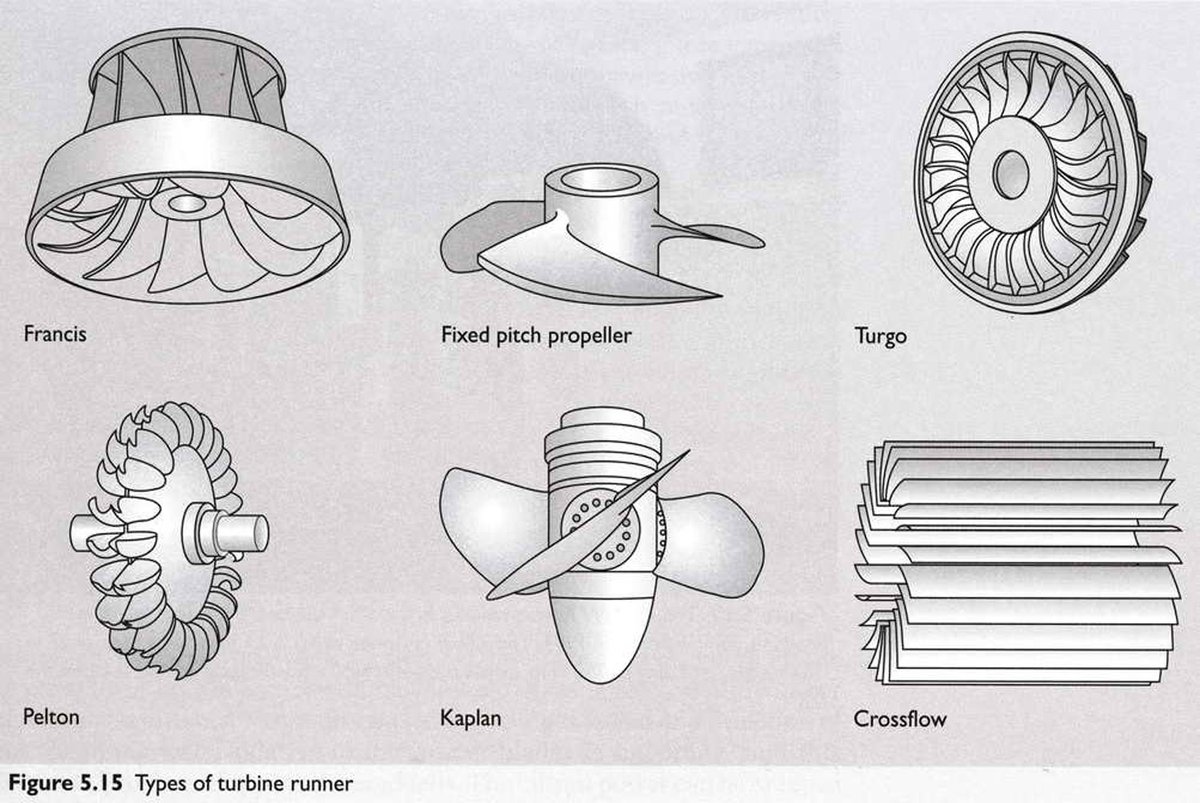

- Key Components: Turbines (Pelton, Francis, Kaplan), a shaft, a rotor (with electromagnets), and a stator (with wire coils).

- Main Turbine Types: Impulse (high head/velocity, e.g., Pelton) and Reaction (pressure difference, low-to-medium head, e.g., Francis, Kaplan).

- Major System Types: Conventional (dam/reservoir), Run-of-River (no large dam), Pumped Storage (energy storage), Tidal, Wave, In-stream, and Micro Hydro.

- Big Benefits: Renewable, reliable, stable, long lifespan, quick start-up, no emissions, energy storage, consistent.

- Key Challenges: High upfront cost, environmental impact (ecosystem disruption, fish migration), geographical limits, potential impact on marine life.

- Future Role: Critical for climate change mitigation, grid stability, and integrating intermittent renewables like solar and wind.

The Power of Water: How Hydro Generators Work

At its core, a hydro generator is an elegant dance between water, magnets, and wire. It's a testament to Michael Faraday's groundbreaking discovery of electromagnetic induction: when a conductor moves through a magnetic field, it generates an electric current. For hydro, that conductor is a coil of wire, and the movement comes from water.

From Potential to Power: The Physics Behind It

Here’s the simplified flow: Water, often held at a certain elevation, possesses potential energy. When this water is released, usually through a penstock (a large pipe), its potential energy converts into kinetic energy – moving water. This moving water then strikes or flows past the blades of a turbine.

As the turbine spins under the force of the water, it drives a central shaft. This shaft is directly connected to the generator’s rotor, which is essentially a giant assembly of powerful electromagnets. As the rotor spins, its magnetic field changes relative to the stationary coils of wire in the stator surrounding it. This changing magnetic field is the magic spark that induces a voltage in the stator coils, producing the electrical power we use every day.

It's a marvel of mechanical and electrical engineering, transforming a natural force into a controlled, clean energy output. To truly grasp this incredible process, you might want to Learn about hydroelectric generators in more detail.

Anatomy of a Hydro Generator: The Core Components

To appreciate the "types" of hydro generators, it helps to understand their fundamental building blocks:

- Turbine: This is the first point of contact with the water. Different turbine designs are optimized for varying water conditions (head and flow), as we'll explore shortly. Think of it as a highly specialized water wheel.

- Shaft: A robust mechanical linkage that transfers the rotational energy from the turbine to the generator.

- Rotor: The spinning part of the generator. It houses powerful electromagnets that create the magnetic field crucial for electricity generation.

- Stator: The stationary outer casing of the generator, containing meticulously arranged coils of copper wire. This is where the electrical current is actually induced and collected.

Each component is engineered to withstand immense forces and operate continuously for decades, a testament to the robust nature of hydroelectric power.

The Diverse World of Hydro Generators: Types and Technologies

When we talk about hydro generators, we're not talking about a single, monolithic technology. The ingenuity of engineers has led to a wide array of designs, each optimized for specific geographical conditions, water availability, and energy demands. We can broadly categorize them by the type of turbine they employ and the overall system design.

Turbine Types: The Heart of the Flow

The choice of turbine is paramount, dictated primarily by two factors: "head" (the vertical drop of water) and "flow" (the volume of water).

Impulse Turbines: High Head, High Speed

Impulse turbines are designed for situations where there’s a significant vertical drop (high head) and relatively low water volume. They operate by converting the water’s potential energy into kinetic energy before it hits the turbine. A nozzle directs a high-velocity jet of water onto specially shaped buckets or blades, causing the turbine to spin.

- Pelton Wheel: The quintessential impulse turbine. It features a series of double-cupped buckets arranged around a wheel. The water jet strikes the divider in the middle of each cup, splitting the flow and efficiently transferring momentum. Pelton wheels are highly efficient in high-head applications, sometimes even at relatively low flow rates. Think of dramatic mountain rivers with steep drops.

Reaction Turbines: Pressure, Power, and Versatility

Reaction turbines, by contrast, are fully submerged in the water flow and derive power from the pressure difference across their blades, as well as the kinetic energy of the water. They are typically used in low to medium-head situations with large volumes of water.

- Francis Turbine: This is arguably the most common type of hydro turbine globally, a true workhorse. It's a mixed-flow reaction turbine, meaning water flows radially inward toward the runner and then axially out. Francis turbines are incredibly versatile, efficient across a broad range of heads (from tens to hundreds of meters) and flow rates. They are often found in large conventional hydroelectric dams.

- Kaplan Turbine: A propeller-type reaction turbine, the Kaplan is ideal for low-head, high-flow applications. Its most distinctive feature is its adjustable blades, similar to an airplane propeller, which allow it to maintain high efficiency even when water flow fluctuates. This makes it perfect for run-of-river systems or sites with significant seasonal changes in water levels.

Hydro Energy Systems: Harnessing Water Differently

Beyond individual turbine designs, the overall system in which hydro generators are deployed also varies significantly. These system types define how water is managed and utilized for power generation.

Conventional Hydroelectric: The Reservoir Giants

This is what most people visualize when they think of hydropower: a large dam creating an expansive reservoir. Water is stored behind the dam, building up significant potential energy due to the high head created. When electricity is needed, water is released through intake gates, flowing down penstocks to turn turbines and generators.

- Applications: Provides massive, consistent power generation, flood control, irrigation, and recreational opportunities. Crucial for base-load power.

- Considerations: High upfront construction costs, significant environmental impact (ecosystem disruption, potential displacement of communities).

Run-of-River: Flowing with Nature

Run-of-river systems divert a portion of a river’s flow through a channel or penstock to a turbine, then return the water downstream. Crucially, they typically do not require a large dam or reservoir. Some might have a small weir to create a minimal head.

- Applications: Environmentally friendlier than conventional hydro, suitable for rivers with consistent flow, powers local grids.

- Considerations: Generation capacity is directly dependent on natural river flow, making them less flexible during droughts or seasonal variations.

Pumped Storage: The Grid's Water Battery

Pumped storage hydropower (PSH) doesn’t generate net electricity but acts as a giant energy storage system. During periods of low electricity demand (and often when excess power is available from other sources like wind or solar), it uses that electricity to pump water from a lower reservoir to an upper one. When demand for electricity peaks, the stored water is released from the upper reservoir, flowing downhill through turbines to generate power, much like a conventional hydro plant.

- Applications: Critical for grid stability, balancing supply and demand, integrating intermittent renewable sources, and providing rapid response during peak loads.

- Considerations: Requires specific geography (two reservoirs at different elevations), high capital cost, can impact aquatic life during pumping/generating cycles.

Tidal Energy: Taming the Ocean's Rhythms

Harnessing the predictable ebb and flow of ocean tides, tidal energy systems are a powerful, albeit geographically limited, form of hydro.

- Tidal Barrages: Similar to conventional dams, these are built across an estuary or bay. As the tide comes in, water is allowed to flow through sluice gates into the barrage, and then as the tide goes out, the trapped water is released through turbines to generate electricity.

- Tidal Stream Generators: Resembling submerged wind turbines, these devices are placed in areas with strong tidal currents, directly harnessing the kinetic energy of the moving water without requiring a barrage.

- Applications: Highly predictable power generation, long operational lifespan.

- Considerations: Very high construction costs (barrages), potential impact on marine ecosystems, specific geographical requirements (sufficient tidal range).

Wave Energy: Surfing for Power (Still Emerging)

Wave energy captures the kinetic energy from the up-and-down motion of ocean waves. Unlike tidal energy which relies on horizontal movement, wave energy focuses on vertical displacement. This technology is still largely in its developmental and demonstration phases, with various innovative device designs.

- Applications: Future potential for coastal communities, distributed power generation.

- Considerations: High cost, technical challenges in harsh marine environments, impact on marine life not fully understood.

In-Stream Hydropower: Submerged, Silent Power

Similar in concept to tidal stream generators, in-stream hydropower involves placing turbines directly into rivers or ocean currents without the need for dams, diversions, or barrages. These are often smaller scale and designed to minimize environmental impact.

- Applications: Utilizing existing river flows without major infrastructure, suitable for remote areas.

- Considerations: Limited generation capacity, potential impact on aquatic life due to turbine interaction.

Micro Hydropower Systems: Powering the Personal Scale

Micro hydro refers to very small-scale hydroelectric installations, typically generating less than 100 kilowatts. These systems are often used by individual homes, farms, or small communities, particularly in remote or off-grid locations. They usually employ simpler turbine designs and require a consistent water flow from a small stream or river.

- Applications: Providing decentralized power, self-sufficiency, powering isolated communities without grid access.

- Considerations: Limited generation capacity, requires consistent local water flow, maintenance needs specific expertise.

Applications: Where Hydro Generators Make a Difference

The diverse types of hydro generators translate into an equally diverse range of applications, each playing a crucial role in our energy landscape.

Powering Cities and Industries

Conventional hydroelectric power plants, particularly those with large reservoirs and Francis turbines, are stalwarts of national grids. They provide reliable, base-load electricity, capable of powering millions of homes and demanding industrial operations. Their immense scale makes them a cornerstone of clean energy for developed and developing nations alike.

Grid Stability and Renewable Integration

This is where pumped storage hydropower truly shines. As solar and wind power become more prevalent, the challenge of their intermittency grows. When the sun doesn't shine or the wind doesn't blow, the grid needs a way to balance supply and demand instantly. Pumped storage acts as a giant "water battery," absorbing excess power when renewables overproduce and delivering it back to the grid within minutes when demand outstrips supply. This capability is absolutely vital for a stable, high-renewable grid future.

Remote Community Electrification

Micro and run-of-river hydropower systems offer a lifeline to communities far from conventional power grids. Imagine a village nestled in a mountain valley, using a small stream to generate its own electricity, transforming daily life without needing expensive grid extensions or relying on fossil fuels. This decentralized approach fosters energy independence and improves living standards.

Water Management and Beyond

Beyond electricity generation, many hydroelectric projects, particularly conventional dams, serve multiple purposes. They are critical for flood control, storing excess water during heavy rainfall and releasing it gradually. They can also provide a stable water supply for irrigation in agriculture and ensure drinking water for urban areas. The infrastructure often supports navigation, fisheries, and even tourism, making them complex, multi-functional assets.

The Upside: Why Hydro Power Shines Bright

Hydroelectric power offers a compelling suite of advantages that secure its place as a leading renewable energy source.

- Truly Renewable: Powered by the water cycle, as long as rivers flow and rain falls, hydropower is perpetually available.

- Reliable and Consistent: Unlike intermittent sources, hydro plants can operate continuously, providing a stable, predictable power supply.

- Long Lifespan & Low O&M: Hydroelectric power plants are built to last, often operating for 50-100 years or more with relatively low ongoing operation and maintenance costs compared to their initial investment.

- Quick Start-Up: Many hydro generators, especially pumped storage and smaller conventional units, can ramp up to full power very quickly, making them excellent for meeting sudden peaks in electricity demand.

- Zero Emissions: Once built, hydroelectric generators produce no greenhouse gases or air pollutants during operation, significantly contributing to climate change mitigation.

- Energy Storage Capability: Pumped storage isn't just a generator; it's the largest, most effective form of grid-scale energy storage available today.

- More Predictable: While river flows can vary seasonally, they are generally more predictable than wind or solar patterns, allowing for better energy planning.

Navigating the Currents: Challenges and Considerations

Despite its impressive advantages, hydroelectric power is not without its complexities and drawbacks. A responsible approach requires a clear understanding of these challenges.

Environmental Footprint: A Delicate Balance

The most significant concerns revolve around the environmental and ecological impacts.

- Habitat Disruption: Large conventional dams can drastically alter river ecosystems, creating reservoirs that flood vast areas of land, destroying natural habitats, and displacing wildlife.

- Fish Migration: Dams impede the natural migration routes of fish, particularly anadromous species like salmon, which need to move upstream to spawn. Fish ladders and other mitigation efforts can help, but aren't always fully effective.

- Water Quality Changes: Reservoirs can alter water temperature, oxygen levels, and sediment transport downstream, affecting aquatic life.

- Methane Emissions: While not directly emitting air pollutants, reservoirs can be sources of methane (a potent greenhouse gas) from the decomposition of submerged organic matter, especially in tropical regions.

Economic Realities: High Upfront, Long-Term Value

Building a hydroelectric power plant, especially a large-scale conventional or pumped storage facility, requires an enormous initial capital investment. The planning, engineering, and construction phases are lengthy and costly. However, these high upfront costs are typically offset by the plant's exceptionally long operational life and very low fuel (water) costs.

Geographical Constraints: Not Every Location Fits

Certain types of hydro power are highly location-specific:

- Pumped Storage: Requires two naturally occurring or artificially created reservoirs at different elevations, close enough for efficient water transfer.

- Tidal Energy: Needs coastlines with a significant tidal range and suitable bay or estuary morphology for barrages, or strong currents for stream generators.

- Wave Energy: Demands consistent, powerful ocean waves and resilient infrastructure to withstand extreme marine conditions.

- Micro Hydro: Relies on consistent small stream flow, which isn't universally available.

Impact on Aquatic Life: A Continuous Challenge

Beyond migration issues, the very act of water passing through turbines can harm fish and other aquatic organisms. While turbine designs are improving to be more "fish-friendly," it remains a significant concern for in-stream and run-of-river systems. Sedimentation behind dams can also deprive downstream areas of vital nutrients.

The Future Flow: Hydro's Indispensable Role in a Sustainable World

Hydroelectric generators are not just a legacy technology; they are absolutely critical for global efforts to mitigate climate change. By providing a massive source of clean, renewable electricity, they dramatically reduce the carbon footprint of power generation. Currently, hydro accounts for about 16% of global electricity production and remains the largest contributor among all renewable energy sources, supplying over 60% of total renewable generation.

Technological advancements continue to push the boundaries, leading to more efficient turbine designs, better environmental mitigation strategies, and the expansion of small and micro hydro systems that are less environmentally disruptive. These smaller-scale solutions offer a pathway to decentralized power generation and energy access in remote areas.

The future of hydro is also inextricably linked to the rise of other intermittent renewables like solar and wind. Pumped storage hydropower, in particular, is an unsung hero, providing the essential "flexibility and storage" glue that allows grids to reliably integrate ever-increasing amounts of intermittent renewable energy. Without its ability to balance supply and demand quickly, the transition to a fully renewable energy system would be significantly more challenging and less stable.

Your Hydro Generator Questions, Answered

Q: Are hydro generators bad for the environment?

A: Large conventional hydro projects, especially those with dams and reservoirs, can have significant environmental impacts, including habitat destruction, disruption of fish migration, and changes to water quality. However, technologies like run-of-river, in-stream, and micro hydro systems aim to minimize these impacts. The overall environmental benefit of generating clean, emission-free electricity usually outweighs these concerns, especially with modern mitigation efforts.

Q: How long do hydro generators last?

A: Hydroelectric power plants have an exceptionally long lifespan, often operating for 50 to 100 years or more with proper maintenance. This makes them one of the most durable forms of energy infrastructure.

Q: Can hydro generators be used in any river?

A: No, not every river is suitable. Hydro generators require specific conditions, primarily sufficient "head" (vertical drop) and "flow" (volume of water). Different turbine types are designed for different combinations of these factors. Some rivers may be too shallow, too slow, or have protected ecosystems that preclude development.

Q: What is the difference between an impulse and a reaction turbine?

A: Impulse turbines (like Pelton wheels) use the velocity of a high-pressure water jet to spin, best for high-head, low-flow scenarios. Reaction turbines (like Francis and Kaplan) are fully submerged and use the pressure difference of the water flow to generate power, best for low-to-medium head, high-flow scenarios.

Q: Is hydropower expensive?

A: The initial construction cost of large hydroelectric projects is very high, often billions of dollars. However, the operational costs (no fuel, low maintenance) are very low over their exceptionally long lifespan, making them very cost-effective in the long run.

Beyond the Blueprint: Embracing Hydro's Potential

The journey through the types and applications of hydro generators reveals a fascinating landscape of innovation, power, and environmental responsibility. From the ancient, steady turn of a water wheel to the cutting-edge submerged turbines harnessing ocean tides, hydropower remains a vital, evolving force in our quest for a sustainable energy future.

Understanding these systems is not just an academic exercise; it's about recognizing the intricate balance between human ingenuity and natural forces. As we continue to decarbonize our grids and electrify our societies, the strategic deployment and intelligent management of hydro generators, in all their diverse forms, will be absolutely essential. It’s a powerful reminder that sometimes, the oldest solutions, continually refined, are still our strongest allies in building a cleaner, more reliable world.